These objects which connect us to the others

Jul 2013

Text: Adeline Rispal

When I wrote this paper late 2010 for the ICMAH conference in Shanghai “Original – Copy – Fake / On the significance of the object in history and archaeology museums”, headed by the historian and curator Marie-Paule Jungblut, we where working on a competition for the Musée-Cité of Economy and Currency for the Bank of France in Paris. In this project, as in any other, what we where attempting to highlight in the museum spaces was the complexity of human mechanics. It was the opportunity to think about the notions of value and exchange.

Trust

Just as the global economic system is based on confidence in the value of market exchange, which until World War One was founded on gold bullion stored in state depositories and is today based on economic growth and the balance in national budgets, one could say that the heritage and museum system – particularly in the West – is founded on trust in the authenticity of art works and artefacts housed in museums and monuments open to the general public.

In 1929, we saw what loss of confidence in the western economic system engendered. More recently, the spectre of this recession again hovered above us. European and other world states and institutions had to guarantee the system so as to avoid a domino effect.

What would happen if museum collections were discovered not to be entirely authentic? If some of their exhibits were fakes or copies?

The owners of public collections – the nation’s citizens – would surely be alarmed to see their treasures vanish into thin air, their beliefs in the greatness of their culture assailed by doubt.

Would visitors continue to queue up outside the world’s greatest museums or would they desert monuments and museums?

Would the market for fakes flourish and, being accessible to a far larger public, become even more profitable than the market for originals?

Would curators recycle themselves into captains of the culture industry or would their role be limited to conserving a few original pieces excluded from the market system and stored in “Museums of Originals”?

Would countries and local authorities be able to avoid the domino effect? Would they be criticized for having invested vast amounts of money in building sanctuaries for fakes? Or would they be congratulated for having spent less on preventive conservation and security for objects that no longer needed them?

Should European and worldwide institutions demand that non-authentic collections be eradicated and thus succeed in protecting what governments would fail to do? Or should they stand by and witness the total redistribution of genuine and counterfeit heritage on a global scale, to the great satisfaction of countries stripped of their own cultural heritage?

And what would become of humanity’s symbolic relationship with these objects? How would we remain linked to our ancestors, our predecessors? How would we obtain proof of their experience that fosters ours?

How would we have access to the artistic expression of their doubts and suffering that helps us endure ours? How would we gain access to the expressions of other civilizations, of other forms of thought and relationships with the world?

Could we live without the symbolic – emotional – impact attributed to objects that mean something to us? Or would we adapt to this new order by attaching no more importance to a recently purchased pipe than to one belonging to our late husband?

How would our emotions find their way in this true-and-false maze? What would have to be invented to catalyze a feeling of belonging to our culture, the social cohesion of our communities?

FULL PAPER BELOW

( Fullscreen and download here )

A poet should leave traces of the path he has trodden, not evidence. Only traces inspire dreams.

René Char

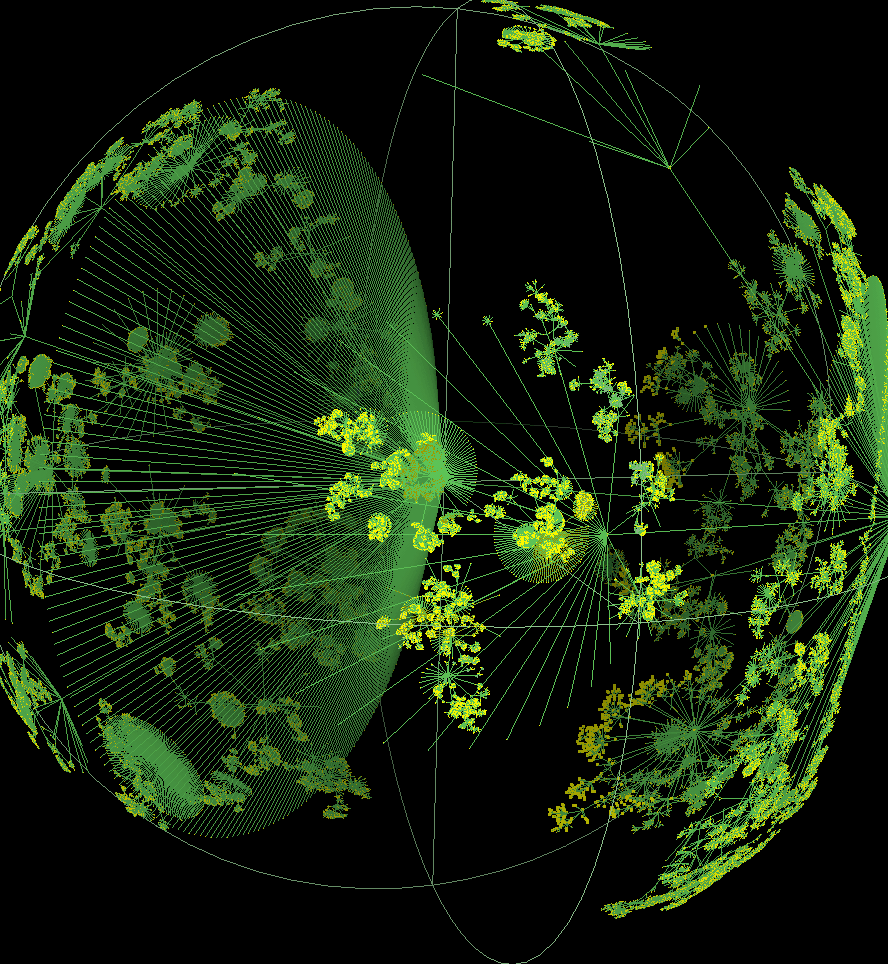

image d’intriduction : Caida visualization tools https://caida.org/tools/visualization/